In a country like Japan that traditionally values permanent employment, flexible employment practices such as freelance or gig work have always been fairly uncommon. So ingrained is the concept of lifetime employment in Japan that there is a term for it: shūshin koyō.

Business theorist and economics professor James Abegglen is believed to be the first to describe this system of lifetime employment. In his 1958 work The Japanese Factory: Aspects of Social Organization, Abegglen mentioned a socio-cultural phenomenon in Japan where employers value and reward employee loyalty and commitment. This commitment is deemed to be an integral norm in the Japanese business management culture.

Lifetime employment, a distinctive characteristic of Japan’s postwar labor system, begins when an employee is hired after graduating from a university and is expected to be part of the company until retirement. Image Source: Tokiotours

Japan’s Lifetime Employment Tradition

Sociologist Kazuo Yamaguchi’s study called “The State and Change in the “Lifetime Employment” in Japan: From the End of War Through 1995” distinguished between two elements of lifetime employment: the first as the employer’s policy and the second as the employees’ commitment. Viewed as the employer’s policy, this lifetime employment is “a system in which the employer refrains from dismissal or lay-offs of full-time regular employees for management reasons.”

On the other hand, seen as the employees’ commitment, lifetime employment provides job security. Employees show commitment “to not leave or switch employment until they reach retirement age once they have secured a full-time regular position with their employer.”

From Yamaguchi’s perspective, the following are basic requirements to keep lifetime employment viable: first, “employers expect that demand in the workforce will grow, or remain unchanged in the future;” and second, that “the benefits gained from securing employees’ long-term commitment are greater than benefits gained from maintaining flexibility in terms of adjustment of the employee population.”

Under this system, employees gain a number of company-specific skills since they are regularly promoted and transferred within the same company. That is to say, they master the different aspects of the work in which the company is engaged.

Initially, this system was fairly reliable and consistent, but it showed signs of slowing down around 1989, with the collapse of the country’s bubble economy.

More Flexibility towards Freelancing

Since then, Japan has shown signs of trading its preference for stability and loyalty for more flexible freelancing opportunities, or at the very least, considering the latter.

The Financial Times explains: after the bubble economy collapse, “companies stopped recruiting graduates and replaced them with workers on temporary contracts. So, the system has “seized up” in the way a car does when it is not regularly serviced.”

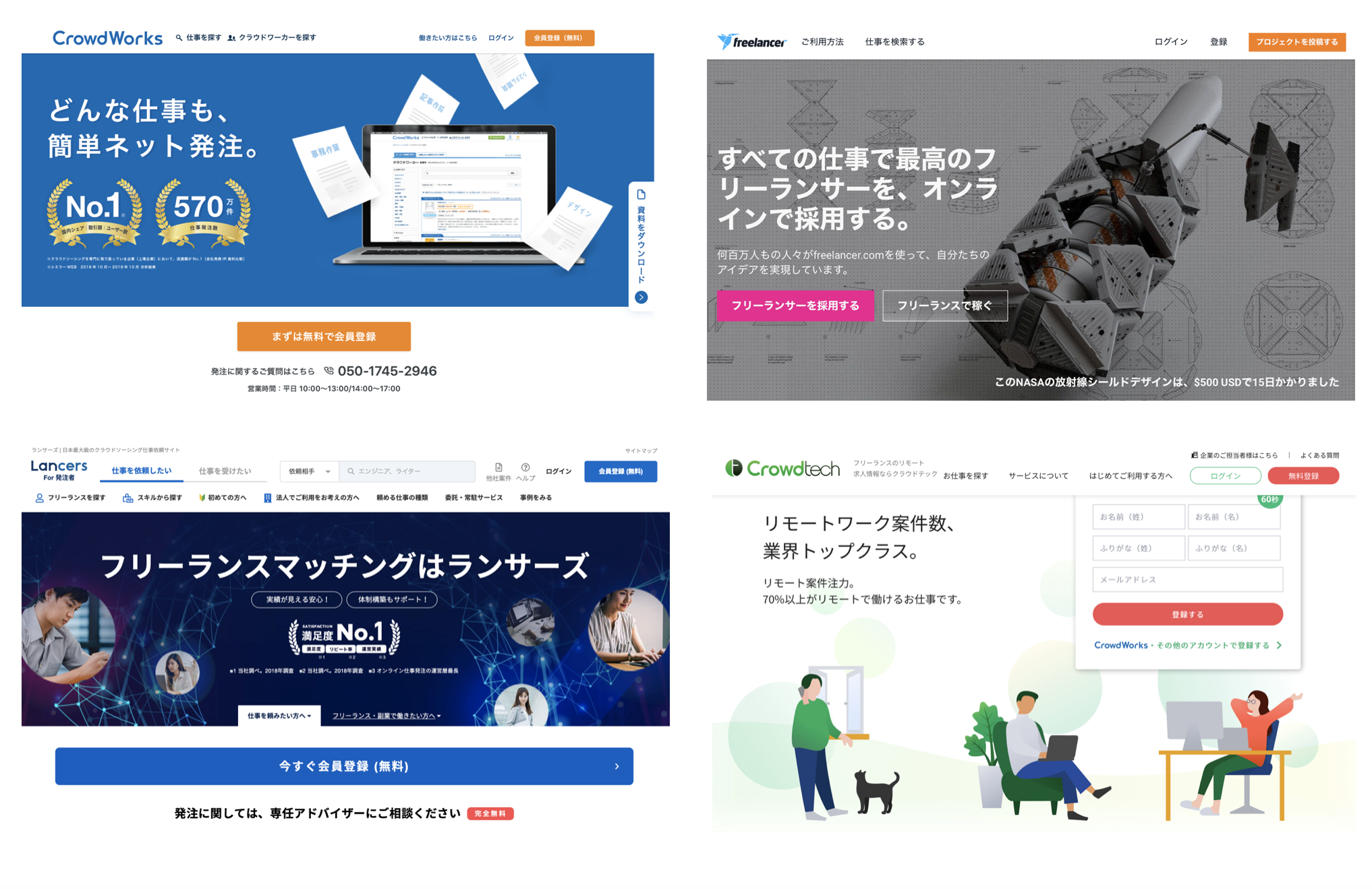

This phenomenon finds support in a report published in 2018 by Lancers, one of the leading digital agencies connecting crowdsourcing services with professionals in Japan. The report found that Japan’s freelancing community saw a 23% growth from 2015 to 2018. Further, as of 2018, some 7.44 million Japanese—around 11 percent of the workforce—were estimated to have taken on at least two jobs.

The freelance work opportunities also have a wide range. Among these are consulting work, web design, writing, engineering, translation and interpretation, sales and marketing, and public relations.

Image Source: Live Work Play Japan

In other words, Japan appears to be warming up to the gig economy, moonlighting, part-time work, and freelance trade in ways that would have been previously hard to imagine.

Unlike lifetime employment, freelance work provides flexibility, independence from a single company, better control over one’s workload, and the freedom to take on a variety of tasks and projects.

Responding to this attitude shift, several local talent marketplaces have also emerged, including @SOOH, Crowdtech, IT kyūjin Nabi, GeechsJob, Workshift Solutions, Coconala, and Levtech. Japanese workers are also said to have an active presence on international gig economy platforms, such as Upwork and Fiverr.

Japan’s Gig Economy: Challenges

Meanwhile, the Japanese government has begun providing some support, such as reviewing guidelines on protecting freelance workers and checking insurance coverage and policies to promote the flexible working setup.

That said, many challenges remain for Japan’s growing freelance and gig workers. In 2020, Shigeki Morinobu wrote in “Toward a Safety Net for Independent Workers” that the COVID-19 crisis exposed some of the worries of Japan’s gig economy. There is the challenge, for instance, of a volatile income and the pressure of the responsibility for one’s personal economic security. Unlike regular payroll employees, gig workers are also not covered by the Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance, Employment Insurance, and Employees’ Health Insurance, Morinubu claims.

Other concerns include sporadic work opportunities and cash flow issues such as collecting payment from clients, some of whom turn out to be fraudsters. Because of its independent nature, freelance work likewise provides little opportunity for socialization with members of a team or co-workers at a company, contributing to feelings of isolation.

Protesters in Japan calling for legal protection for freelance workers. Image Source: Japan Times

Many employers also show a reluctance to allow their workers to take on more than one job. Reportedly, some companies similarly show prejudice towards former freelancers, deeming them to be “ill-equipped for jobs and not up to date with the industry,” according to Zoho.

Meantime, the pandemic dealt a huge blow to freelance work in Japan, with gig workers saying they experienced reduced work opportunities, according to an Intloop survey.

Finally, there remains the question of whether freelance work enjoys socio-cultural acceptance, given the debates on whether it is as sustainable or stable as regular lifetime employment.

With these hurdles, it is no surprise that Japan’s current gig economy is quite low compared to other markets like the United States or Europe. Nonetheless, the shift in the values and attitudes of Japanese workers is unmistakable and merits due attention. In many ways, this shift is reshaping mindsets, changing employment practices, and influencing state regulation. Moreover, it is calling into question established traditions such as shūshin koyō, or strong preference for stability over flexibility. Perhaps it is even opening us to new ways of conceiving of the relationships and intersections among labor, technology, culture, and the global market.

Main image source by Brooke Cagle on Unsplash