According to the Center for Urban Design and Mental Health UD/MH, cities are associated with higher rates of most mental health problems compared to rural areas: an almost 40% higher risk of depression, over 20% more of anxiety, and double the risk of schizophrenia, in addition to loneliness, isolation, and stress. The Covid pandemic has highlighted the need to put people first and create livable cities. The Nagaoka Review team had the opportunity to speak with an Italian architect and assistant professor at the University of Montreal – School of Architecture, Alice Covatta, about her interdisciplinary research on connecting urban design and mental health.

NR: Alice, before talking about your urban design and mental health research project, could you tell us about your educational background, career, and architectural experience? Who is Alice Covatta?

AC: I’m an architect, researcher, and tennis player. After achieving a degree at IUAV University of Venice in 2010 and a Ph.D. with the highest distinction in Architecture and Urban Design from the University of Udine, I started to interconnect design with research. I spent a long time working in companies and universities in Europe, Japan, and today Canada, trying to deal with projects that impact the quality of public spaces. That said, I’m interested in designing better cities to raise our quality of life and stimulate new ways to appropriate our public domain that goes hand to hand with people’s wellbeing. So, I’m always looking for new projects that propose connections, porosities, juxtapositions, and overlapping functions to enhance the sense of inclusion, and at the same time can provide a sort of intimacy, a sort of feeling of, well, wealth while being both in the community but both alone. If we think of architecture and spatial design as atmospheres, we don’t always want to position our bodies in a crowd. Instead, we need alternation and diversity of our sensory experience. Although public space can’t oblige people to interact, it can trigger our “milieu de vie,” make places valuable and attractive and ultimately erase barriers.

Image of Alice’s personal exhibition “Yamanote-sen” at the Candiani center in her hometown Mestre (Italy). Image courtesy of Alice

Two of my dearest cities are excellent examples in this sense. The urban structure of Venice public spaces beats in compression and expansion; its rhythm moves through narrow “calli” – this word is untranslatable, but we could say it is the Venetian term for street – and suddenly open up to a large and vibrant “campo” – other unique Venetian word which means square. The urban language is multiple, faceted, and provides infinite choices, and there is a hidden order that subtended a sensual relation with the user. This can indicate a significant discount of space flexibility in Japan because we have a super crowded and interactive public space (like Shibuya), and immediately right after a very intimate one where you can feel this sense of connection between people and nature. In Japan, there is no clear jerky; it’s like everything is moving. It’s a flux, and this flux inspired me to pursue a doctorate followed by a PostDoc in architecture, where I studied public space in dense cities and the Japanese-specific contexts.

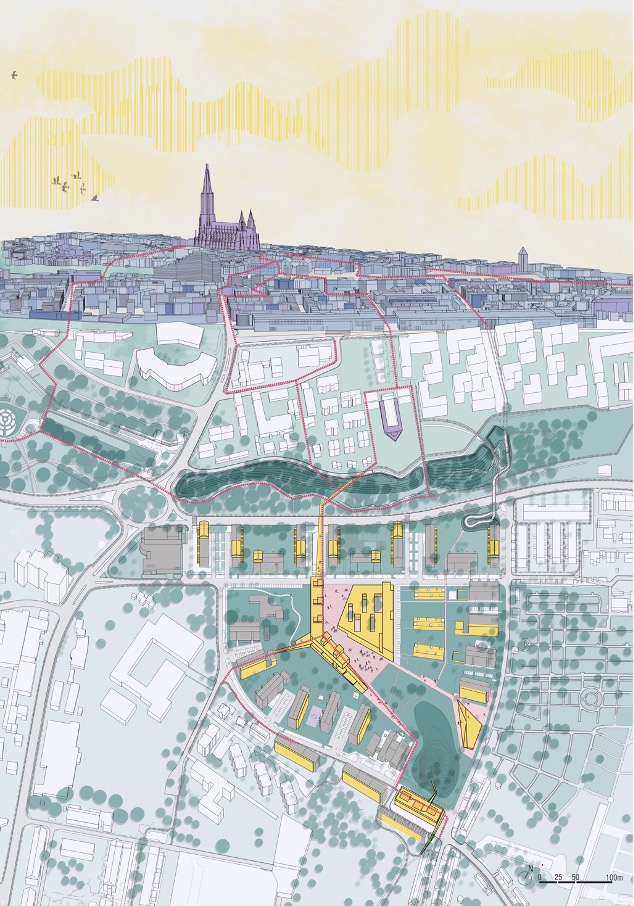

And six months ago, I moved to Canada to teach urban design and architecture at Université de Montréal – School of Architecture. Also, here in Canada, together with 12 students, I have a design studio. One of our projects is based on rethinking a small city in Sweden, a town undergoing considerable demographic growth. Our concept called “urban fertilizer” is how to frame architecture with a robust public presence that can connect the community and provide quality of life in a city that is changing its identity rapidly.

Poster of Alice Covatta’s design studio “Urban Fertilizer” (Engrais Urbain in french), Universiteé de Montreal. Image courtesy of Alice

NR: You are a successful architect and also an academician guiding new architects. How does it feel to shape the future of both the buildings and their possible architects?

AC: Even at university and my studio, it is exciting and reinforcing to see students come to the same insights and have the same epiphanies that I experienced and watch them fight the good fight and do great things. Their enthusiasm and perseverance remind you of the reason that you did this in the first place. I am trying to support their sensibility, push their creativity, and develop a critical understanding of how cities are changing and the hidden forces that are shaping them (most of the time driven only by economic interest).

NR: What advice you give to your young students/architects?

AC: If it’s possible, go and see many places and center yourself, respecting your uniqueness. Experience cities and nature, study them, understand people’s perspectives, embrace cultural diversity and human rights, contaminate architecture with other disciplines. In this way, you can develop your values and beliefs.

Group photo at Keio Architecture CDW Events, Keio Hiyoshi Campus, Japan. Image courtesy of Alice

Urban planing and Mental Health

NR: In the past years, you have been investigating the fast growth of urban settings in Asia, particularly in Tokyo, and its consequences for mental health. How can Urban Design Impact Mental Health?

AC: Urban design holds exciting potential in population mental health as cities are associated with more and more mental health problems related to their densification and growth. This is disappointing, but cities affect our mental health, and mental health problems significantly impact cities. This creates a vicious circle. As the world’s population transitions to becoming primarily urban, several factors are associated with urban living that can affect mental health, such as poverty, unemployment, overcrowding, noise pollution, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of green space.

But we also have new research that provides critical insight into how we can develop strategic design decisions considering primarily citizens’ health. For instance, Canadian researchers recently unravel the relation between specific architectural residential typology and isolation phenomenon, one of the leading causes of severe mental health issues (especially during the COVID19). The survey shows how high-rise residential buildings are linked more to isolation due to short term (lack of permanence, short renting periods), crowding (sense of inadequate perceived available space), lack of exterior exposure, too many strangers, distance, and lack of buffer zones. Instead, courtyard house typology can be seen as a catalyst to social interaction and well-being because it promotes a sense of belonging to the community and, in the meantime, respect individual privacy. These findings are essential and bring hope for improvement!

NR: What makes a well-designed urban environment?

AC: Creating harmony in everyday lives. Today’s urban design needs to design better cities ultimately to raise our quality of life, especially in the city’s public spaces, and how to be in harmony with nature and everything around us.

There are so many elements involved in creating a comprehensive design. But in my perspective, some are more urgent, for instance, public spaces designed to reinforce social inclusion and the diversity of user groups over time, quality of the sidewalk and street experience-enhancing walkability and bike-ability, presence of features designed to improve safety and security, and more cities are aiming for a national goal of “10-minute walk to a park” for all residents.

And the main element: people. It is essential to focus on the truth that people are the very heart of cities. To fully realize the potential and value of urban design in promoting mental health and well-being in populations, opportunities must be assessed and exploited by public health experts, urban planners, policymakers, and people. Engaging residents and community members who transferred crucial awareness and lived know-how are at the very basic. Well-designed, flexible, and accessible public places are essential, and their creation should involve citizens at each stage of design and development. This is important because promoting mental health adds value to urban design, which is needed to create prosperous cities worldwide.

Contribution to Domus Magazine. Image courtesy of Alice

Alice’s contribution to the book with the article “Planning a local and global foodscape: Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo”

”Better urban design could improve mental health

Alice CovattaAssistant Professor at Université de Montréal - School of Architecture

NR: What are some of the strategies and solutions to today’s urban health challenges?

AC: Isolation, depression, anxiety, higher rates of stress, spatial injustice, not feeling safe without being in a car, air pollution, and reduced ability to exercise as part of your daily routine are just some of the adverse effects of a poorly designed environment. Japan, and more particularly Tokyo, has a complex relationship with mental health. We identified four critical areas of opportunity as a response to today’s urban health challenges through research. These can be conceptualized and applied using a framework called ‘Mind the GAPS’: green place, active place, pro-social place, and safe place. These four design principles facilitate innovative thinking and promote better mental health and wellbeing. There are significant relationships between accessible green spaces and mental health and wellbeing. Design can support mental health by increasing access to green areas with diverse plant and animal life. Also, regular activity and mental health are closely correlated. There are almost limitless possibilities for designing cities to integrate physical activity into everyday life. From providing accessible, comfortable, and safe active transportation to locating outdoor gyms, playgrounds, actions can be taken to help integrate exercise, social interaction, and a sense of free will into people’s daily routines to promote mental health.

Inspiration, Venetian lagoon landscape. Image courtesy of Alice

Europan 14 winner with “the productive hearth of Neu-Ulm”project, with L.Z.Marchi, P.Medici and A.Romani

In addition, it is also imperative to reduce loneliness and promote positive social interaction. Urban design should foster positive, safe, and natural interactions between people and trigger a sense of community, inclusion, and belonging. And finally, a sense of safety and security is integral to people’s mental health and wellbeing.

”A safe environment may improve accessibility and comfort, and urban design has a great deal to contribute

Alice CovattaAssistant Professor at Université de Montréal - School of Architecture

The COVID-19 pandemic impact

NR: What are the major lessons for urban planning and design after the pandemic?

AC: The social isolation practices experienced during the Covid-19 lockdown have highlighted the importance of ‘social’ and changed people’s perception about home, the workplace, and cities in general. Right now, urban design ought to become a form of spatial medicine, whereby the design of built environments positively contributes to and facilitates human and planetary health as the Covid pandemic has highlighted the need to put people first and create livable cities. Perhaps we won’t get another chance to relook at the designs of our neighborhoods and make our post-Covid world more comfortable.

NR: How will the cities of the future look or should look?

AC: As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to transform lives and ways of living across the globe, it is becoming increasingly clear that after this crisis is over, we will not return as before, and one of the most optimistic expectations shows that we are waiting for a new beginning in our lives. It is the beginning of a change in values, habits, our homes, and cities. Cities of the future must be flexible, make better use of existing space and resources, and adapt to the uncertain, rapidly changing realities.