The Nagaoka Review team had the honor to have an interview with Professor Angela Hondru, also known as the Mother of Japanese language education in Romania, about her thoughts on the concept of “work” from a Researcher’s perspective, her passion for the Japanese cultural festival and the sacred dance called kagura, as well as how traditional festivals could be preserved.

ML: Michelle Lim; AH: Professor Angela Hondru

ML: Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed by our team. Let us start by talking about where you are based, and the latest work or projects you are working on.

AH: I have been living in a modest apartment building in the southern part of Bucharest since 1975. It was the year when Ceauşescu, the president of the former communist Romania visited Japan. The feature reports regarding his visit made me turn on the TV-set whenever something about Japan was telecast. (Otherwise, being too busy, I would seldom touch it!) Moreover, the same incentive made me find my way to the National Library and to the Academy Library every Sunday.

Your question about my latest projects makes me start in the end. I have been dreaming for a long time to be selfish enough and study / do research only for my pleasure, without thinking about results to meet other people’s expectations. The COVID-19 situation seems to help me out. The truth is that I would have liked to continue my research on ema votive plaques, namely on the ema featuring matsuri (“folk observances”) and Kagura (“sacred dances”). I have asked for my friends’ help as I need photos to illustrate them, but nobody can run the venture of visiting shrines. I will have to wait. Besides, such ema are nowadays quite difficult to find. I was shocked to see ema displaying manga instead!

In order to quench my longing for old rituals and folk observances (including those that are no longer in practice), I read. I read as thoroughly as I can books like 日本祭祀研究集成 (Compilation of Research Studies on Japanese Folk Observances) in five volumes. One could say that what I am doing is “play”, but I consider it a part of “work”. I love it to distraction. During my entire career, such work-play activity has frequently resulted in new ideas.

ML: Where do you get your inspiration and drive to continue doing what you do?

AH: I get inspiration from books, video tapes and DVDs stored in my house. In fact, I brought some interesting “aspects” of Japanese traditional culture with me every time I went to Japan. Now I can live virtually surrounded by ancient traditions that will not disappear as they are deeply ingrained in the Japanese soul. Moreover, in my opinion, they can be subjected to eternal re-interpretations, whilst the very potential of being adapted to present situations and feelings accounts for their lasting long.

ML: What do you do in your free time?

AH: If “free time” means time to study, not to waste, I must confess I am free and I have been free all my life. I was free even when I worked according to the schedule, because I was always fond of what I was doing. In fact, I have done three kinds of job: teaching, translating and doing research.

ML: What ignited your interest in Japan and the Japanese culture?

AH: The telecasts on Japan in 1975 and the few prints and literary translations from German or French stored in the two important libraries in Bucharest kept stirring my interest and made me enroll, one year later, in the Japanese Course offered by the Open University. At the beginning there were two groups of 44 students each, but towards the second year only 10-12 students remained and I was the only one to graduate in 1979. In 1978, a year before graduating, my teacher Mr. Kanji Tsushima, Third Secretary of the Embassy of Japan at that time, asked me when his mandate was over not to let the Japanese course “die away” because they would send Japanese lecturers. It was a huge challenge, but I had already been teaching English for a couple of years, so I was at least confident in keeping the students in their desks and knowing how to arrest their attention.

In 1980 I had the great chance to attend the summer courses for teachers of Japanese, organized by the Japan Foundation. In the beginning I felt disheartened, then I plucked up courage, then I lost confidence again… However, the Japanese professors proved to be so tactful and sensitive, that I realized I had but to persevere.

Besides, there were many things that impressed me beyond words: Tokyo – the capital city where the modern and the traditional seemed to co-exist peacefully; the Japanese smile; the unique gardens and many, many others. I cannot help mentioning my participation in Bon Odori in the heart of Tokyo, wearing a hapi coat provided by the Japan Foundation. I remember how for the first time in my life I felt the warmth of the exquisite chawan (tea cup) nestled snugly in the palm of my hands, realizing like this why the Japanese tea tasted differently. I had the opportunity to look through books on matsuri and it is difficult to tell you how they stirred my imagination. The first example that crosses my mind is the Japanese farmers’ appreciation of the part played by their scarecrows. They dedicated to them a matsuri in October to show their gratitude for the good job the scarecrows had done all through summer, braving rain and storm. And they rewarded them with mochi and other foodstuff. What wonderful attitude towards work and duty!

I returned home from Japan with many books and I began learning hard. I did not expect to be rewarded like the scarecrows, but I felt I could not quit it any longer. The more I learned, the more I wanted to know – not only the language but especially things about the Japanese traditional culture. I was meanwhile teaching English as well.

ML: How did you get into translation?

AH: Since there were no Japanese textbooks in Romania at that time, I thought it necessary to systematize the teaching material I gathered, which resulted in Nihongo Nyūmon (“Japanese for Beginners”), published by the Shunposha in Japan in 1983. It was followed by revised editions, then another volume to continue the first, Nihongo II, Practical Japanese Course (several revised editions), as well as other essential learning instruments: 111 Situational Dialogues, Japanese-Romanian Dictionary (the translation of “the Japan Foundation Japanese-English Dictionary”, and partly sponsored by it), Guide to Japanese Literature (two volumes), Japanese Myths and Legends, Japanese Festivals – in the Spirit of Tradition, the entries on Japan and its culture in Encyclopedic Dictionary (5 volumes), Kagura – from Myth to Reality through Dance, Ema – Prayers and Gratitude, guides of conversation, as well as a CD on Japanese Language and Civilization (covering around 3,000 printed pages in all).

At the same time I considered it necessary to introduce Japanese literature. I have translated from Japanese novels belonging to outstanding writers (Yukio Mishima, Sōseki Natsume, Kōbō Abe, Haruki Murakami, Shūsaku Endō, Shūhei Fujisawa, Fumiko Enchi, Osamu Dazai, Sawako Ariyoshi, Teru Miyamoto, Murasaki Shikibu), but also from English translations (Monzaemon Chikamatsu, Eiji Yoshikawa, Lafcadio Hearn). My translations reach around 11,000 printed pages in all.

ML: When translating between languages, how did you overcome the barriers?

AH: I was blessed with an excellent professor during my student years, who was at the same time a famous translator of English literature. He taught us the techniques of translating from English and into English, we practised a lot, and I would always try my hand during the seminars. It is then that I learned that a translator had to master well not only the foreign language he approached, but the civilization as well, to feel every detail to the tip of his fingers, and if possible to get into the character’s skin.

Transposing from one language into another is not only a difficult task due to the dynamism that characterizes each language which carries a culture and a whole way of life, but it also means creative engagement. I realized this aspect best with my own translations and especially when translating The Tale of Genji. I am very proud of “my personal Genji”. After reading the first three chapters in six variants (three in Japanese and three in English), I realized each author or translator had created a “personal Genji”, not at all similar in every detail.

My translating activity went on side by side with teaching. In 1990 I initiated the Department of Japanese Language and Literature within Hyperion University and I started an optional course of Japanese Language at the Academy of Economic Studies. In 1992 I established a special class of Japanese at School 190, and in 1996 at “Ion Creangă” High School.

However, in 1997 I assigned some enthusiastic graduates to my classes at Open University, School 190, and “Ion Creangă” High school. I kept only the classes at Hyperion University and at the Academy of Economic Studies, in order to be able to direct my efforts towards the Ph.D. exams and the thesis The Wedding Ceremonial and the Funerary Ritual in Japanese and Romanian Literatures‘. The thorough study of the rites of passage and their approach from an ethnographic point of view opened for me the door to the postdoctoral Fellowship generously granted by the Japan Foundation in 2000. My long cherished dream finally came true. Since then I have tried to concentrate as much as possible on research. But that does not mean I gave up teaching and translating completely. I could not. After all, there are 24 hours in a day!

ML: How would you define “work” in Research and what similarities can you see with the concept of “work” for an employee in an organization, a student or even being a volunteer?

AH: Research is “work” too, like any other kind of work. I could nevertheless speak here about two kinds of research work: on the one hand, that of an employee who gets money from a Research Institute, I mean he does it as a paid job; in the same way, even if a student does not work for money, he does it with a view to graduating and finding a good job. In both cases, I see their work rather motivated pragmatically. On the other hand, the research of a person who chooses it on his/her own will, ignoring money completely, can rather be compared to that of a volunteer. Not completely, either, because the volunteer has “a boss” who gives him/her directions. Moreover, passion and dedication come to the forefront for the person who chooses to do research without thinking of any reward. I do not exclude them in the case of employees either, but they are for sure fuller of “feeling” in the latter.

After studying matsuri from books for many years, alongside with the topic for my Ph.D. Thesis, I was lucky enough to start fieldwork trips to live matsuri to the quick. It was not only once that I felt that the hearts of the Japanese around were beating at the same time by the portable shrines carrying the celebrated deity or when watching a ritual. And mine was not less elated either.

ML: Tell us more about your excitement regarding festivals in Japan.

AH: Besides the delightful entertainment the matsuri offer, they also enchant through becoming a moving stage on which the history of Japanese culture unfolds. Each of them conveys a message related to the ancient history which pours forth into the precincts of the shrines and into the streets of the towns and villages.

I’d like to mention two examples. Both matsuri take place in big cities, in the same month, but they are completely different.

Sannō-matsuri is a biennial event performed at Hie-jinja, in the heart of the capital city of Tokyo, from 9th through the 16th June, enjoying a history of over five hundred years. It fascinated me with its showy procession on the first day, which consisted of lavishly decorated portable shrines, people on horseback in ancient costumes, musicians maintaining the rhythm of the festival, priests and miko (“shrine maidens”) performing rituals from times immemorial. On the following days, traditional arts were practised in the precincts of the shrine. I enjoyed tea-ceremony, flower arrangements, dance and folk music contests, a drum performance, and Kagura sacred dances. Everything was to my heart’s content.

Photo via Sanno Matsuri Official Twitter account

The other one is Taue-matsuri at Sumiyoshi-taisha in Ōsaka, a kind of archetype for the agricultural rituals related to rice planting. The performance meant to entertain the kami (god) and the spectators included scenes from various historical periods, becoming thus a good opportunity to renew them lest they should sink into oblivion. The “fight” between the two great Clans – Genji and Heike – was mimed by little boys standing in two rows, whilst “the field was ploughed” by two men guiding an ox. While the maidens wearing large sedge hats carried on the rice planting and sang songs of a congratulatory nature, which had been handed down for centuries, some musicians played the flute, accompanied by the drumbeats resounding in the air. Meanwhile dances were performed in the middle of the paddy field. I was extremely impressed by the enthusiasm it aroused amongst the Japanese present in the precincts of the shrine and I understood once again that such enthusiasm (which is really catching!) could protect the identity harassed by a type of modernity alien to the spirit.

ML: What was the biggest challenge you have faced throughout your life as a researcher? Have you ever thought of giving it up?

AH: That is a good question. I had experienced great challenges before and it was painful. Whenever I thought to give up teaching Japanese and translating Japanese literature, I felt like a teenager who had fallen in love fervently but who had to part from her lover. I would weep for a couple of days and then resume my activity as if nothing had happened. Fortunately, after taking up research on matsuri and kagura, not only a single moment did I think of giving it up!

I believe I was blessed during my research, as everything went on smoothly. I recorded details on various matsuri and when I could not grasp the proper meaning, I would ask my advisor, Professor Shunsuke Okunishi. I was so lucky to find myself under the “expert’s baton” of a distinguished folklorist, anthropologist, and renowned specialist in mythology. Professor Okunishi encouraged me and guided me in a way that made me want to discover new and interesting things, and not to limit myself to the information that anyone could find in books.

ML: What made you get interested in Kagura?

AH: On 23rd September 2000 I went to Izumo-taisha with a view to better understanding the individual and collective rituals practised with the ancestors’ cult – topic connected to my postdoctoral research for which I was awarded the generous Japan Foundation Fellowship mentioned earlier. It was then that I discovered Kagura. I dare say “discovered” because until then I had only been familiar with the dances of the miko at the shrines. I was so captivated by the kagura at Izumo-taisha, that I kept watching all the dances for over six hours, despite the persistent rain. I realized I was in fact watching the transposition onto the stage of the myths I had written about in my book Japanese Myths and Legends (1999). It had never crossed my mind they could be staged…

The kagura at Izumo-taisha was only the spark. It went up in larger and larger flames that turned into a blaze… which is still burning bright in my heart. No way to quench it. The field is so vast and charming that all my life could not span the whole of it. The same as with matsuri.

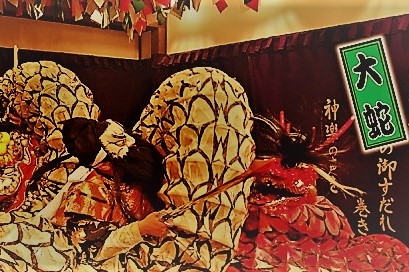

Little by little I understood that in order to shatter the monotony caused by the few artistic elements, Kagura had taken over themes not only from the cosmogony myths, but also from history, legends, and Kyōgen (the farces performed between the Nō plays). This accounts for the variety of kagura performances. Kagura was born out of belief, but it fused with the place and the period of time, being at the same time subject to creativity. In fact, kagura dances follow the same steps as matsuri, being either offerings of music and dance brought to the kami (“deities”) by people, like offerings of food, for instance, or music and dance performed by the kami who descend amongst parishioners.

Briefly, Kagura is an act of communication between deities and community, made possible through performing arts (music, dance, acrobatics, jugglery, and clownery) and disguise (masks and costumes). During such celebratory moments, emotions spring up in the very corners of the soul, shaping a warm and lively world reigned over by the mirth of the event. I felt that in kagura dances we do not speak about a typical actor-spectator connection, but rather about a fluid exchange that wraps them up in shared emotion.

ML: The ritual I liked best among those included in your book entitled Letter to Japan is Shishitogiri (“Wild Boar’s Footprints”), part of Shiromi-kagura. It sounded like a great interaction between the performers, the deities and the society. You mentioned about the dances having their peculiar charm that made you think of the creative energy of the Japanese people. Could you elaborate more on the creative energy that you felt?

AH: Since kagura tells about its origin, about the primordial event that brought it to life, and about cultural developments up to the present day, it becomes real and full of meaning. Each dance seems a challenge to an excursion into the Japanese soul, into his spirituality unspoiled for centuries.

The rhythm – which differs according to region and to type of performance – seems to be inherited. In group dances the performers conjoin and seem to share a single heartbeat. In solo dances the rhythm allows each performer to unveil his own spirituality, eager to bring forth the message of his dance. Many new elements are added by each generation through their creative imagination, which does not seem to cast a slur on the local cultural identity. Gentle torso twists, knee bends, and the more important hand movements which sign different layers of gracefulness – all make it more noticeable the Japanese unique way of interpreting beauty. If we add to this the diversity of exquisite costumes, we will come to envision the Japanese aesthetic values, refined over generations.

Moreover, the humorous remarks and situations which make the audience burst into laughter are to be found in most kagura performances. Joking and dancing prove that, when intertwined, the two attitudes entail true, simple, and refined art.

I think you are right. Shishitogiri is the most amusing part of Shiromi-kagura. Seko and Mabushi, an old couple of kami, enter the mountain in pursuit of an old boar. The old man who seems to be chicken-hearted is urged all the time by his wife. Their gestures are extremely funny, arousing peals of laughter through the dance that lasts for more than an hour. The dialogue of the two kami with one of the high rank priests, who is the so-called “hunting referee”, is full of humour. The irony is mainly directed at the hunters with whom the villagers are familiar, which attests to the importance of hunting in remote mountain villages.

Image by Photo MORIMORI via kagura2.hujibakama.com

In Bicchū-kagura (to give just another example), the dialogue of the clown with the drummer points out all kinds of shortcomings encountered in the immediate community, or matters ripe for ridicule and fun. The drummer often emphasizes the climactic moments of the comic character with strong drumbeats, adding to the humour. I had the feeling that the participants were eager to see whether they were spared ironical remarks, but at the same time confident that their local art will never disappear.

As to Okumikawa-kagura (also known as Hana-matsuri), the dance of Meshinuri and Misonuri who carry little wooden bats tarnished with rice paste and miso paste, respectively, discloses the idea of fertility and rich harvests. They chase people trying to sully their faces; everybody pretends to avoid being dirtied, knowing at the same time that, if they indulge in the ritual, they are invested through contagious magic with healthy and wealthy life. Meshinuri and Misonuri are in no time joined by two Okame – men impersonating fat and dull women – who flirt with the spectators. Licentious behaviour is related to ancient folk beliefs in which night was perceived as a realm of the mysterious and supernatural, when any droll gesture was allowed without being sanctioned. Even though such erotic elements lose their primary significance, through performance they get a new spiritual profile, outlining a certain type of relationship amongst the members of the community.

ML: Would you encourage young people to take part in festivals even if they do not see the need to preserve something they do not understand? What can we do to inspire them to continue the legacy?

AH: Yes. In my opinion, anyone can understand anything if “that thing” is made clear or introduced properly. Tradition is subjected to eternal re-interpretations, whilst the very potential of being adapted to present situations and feelings is very important and could account for its lasting long. Even young people can understand that much.

Along my career as a professor and researcher I came to understand that examples were more effective than talk. During my classes I would show my students hundreds of photos and films, and would tell funny stories in order to stir their interest without their being aware of it. The Japanese professors who knew me could immediately identify which students in Japan belonged to Hyperion University in Bucharest because they all showed interest in matsuri and most of them were even willing to participate actively.

About Professor Angela Hondru

Professor Angela Hondru is a japonologist, translator, ethnologist and was a professor at Hyperion University. Referred to as the Mother of Japanese language education in Romania, she has contributed to the advancement of the Japanese language and culture in Romania through translation work and inspiring students to take an interest in traditional festivals and kagura sacred dances .

She was awarded the prize of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (日本外務大臣賞 , 2008), the Japan Foundation Award for Japanese Language ( 国際交流基金賞 , 2008) and The Order of the Rising Sun, 4th Class, Gold Rays with Rosette ( 旭日小綬章, 2009) .

For more information regarding Professor Hondru, please visit her site.

Please click on “EN” for English