The story behind the birth of domestic macaroni dates back to the Taisho era, a period between 1912-1926, when Japan was moving toward a democratic system of government and modernity ruled Japan’s masses.

But not many people living in the Niigata Prefecture know that Kamo City is the birthplace of locally produced macaroni in Japan.

For the story behind that, I reached out to Yasutaka Yumoto, a researcher and history enthusiast from Nagaoka City, Niigata Prefecture, Japan.

Going Back Into History

“As we all know, macaroni is a staple in Italian cuisine usually used in gratin and salads. Originally born as a type of pasta in Italy, it seems that macaroni reached Japan during the Meiji era (the era preceding the Taisho era),” Yasutaka begins.

“But it was in the Taisho era that the macaroni was first made in Japan. There were three generations of parents and children behind the production of domestic macaroni.”

Yasutaka Yumoto of Nagaoka City, Niigata, Japan.

First Generation: Kichizi

“Kichizi Ishizuki (1864-1919) is one of the first people in Japan to succeed in mass-producing macaroni and contribute to its widespread use. Kichizi ran a small-scale noodle manufacturing business and made dried udon noodles (thick noodles made of wheat flour), and somen noodles (thin version). However, it was his “chicken egg udon”, made by kneading eggs into the noodles, that brought him popularity after winning an Award for Excellence at the 1893 World’s Fair held in Chicago. Some of the iconic products that debuted during that event include the Ferris Wheel, Juicy Fruit Gum, and DeCecco Pasta.”

“In 1908, an importer from Yokohama reached out to Kichizi Ishizuki, showed the macaroni asked if he could make something similar.”

“At that time, macaroni, which was directly imported from overseas, was called ‘perforated udon noodles’ and was considered to be eaten by foreigners. The Japanese people barely knew how to make nor eat it.”

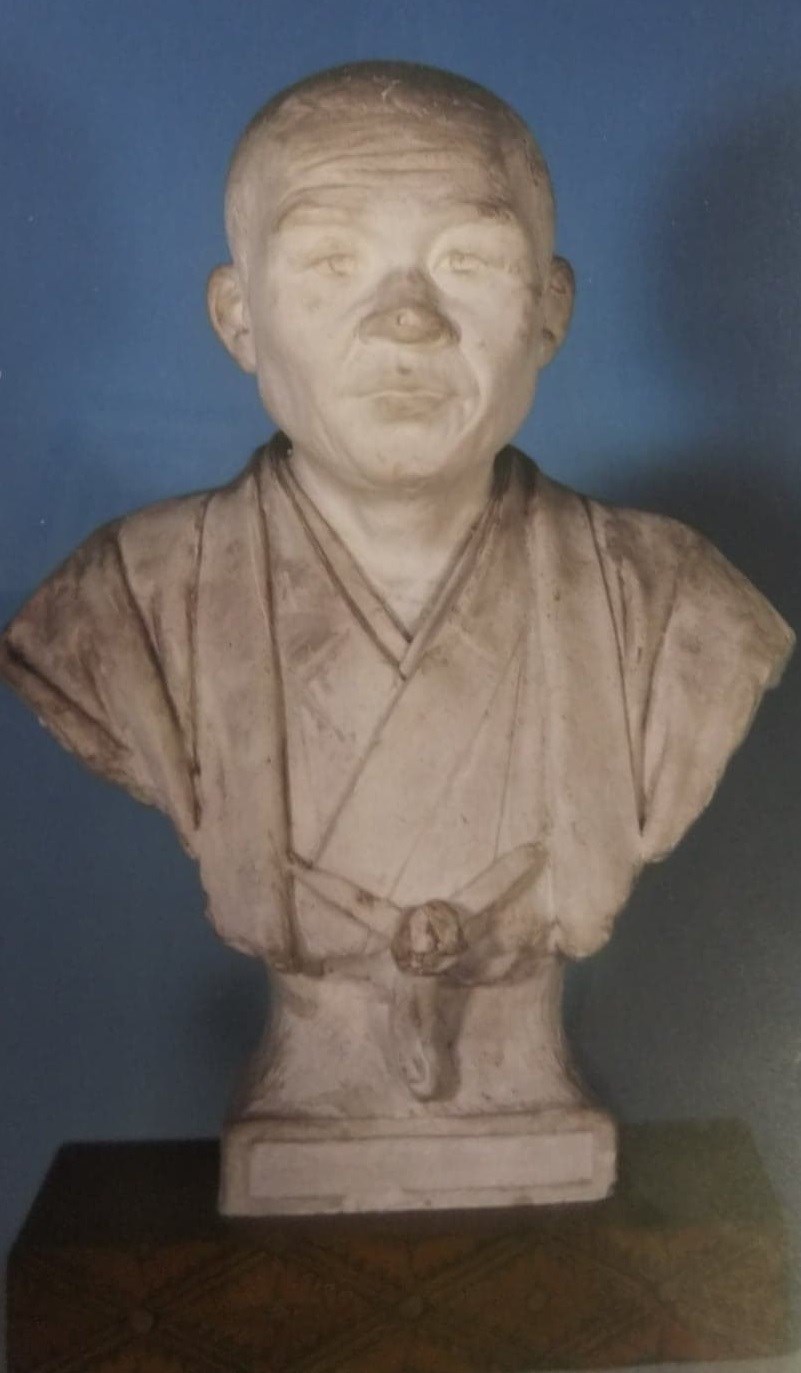

Statue of Kichizi Ishizuki. Photo Credit: Hatsue Ishizuki and Kamo City History Compilation Room

“According to a newspaper article written in the early Showa period, Kichizi Ishizuki started the manufacturing process by building a noodle-making machine. However, no matter how many times he tried, it didn’t work. But Kichizi Ishizuki persisted and after throwing all his fortune into the project, the tenth machine prototype, finally produced something that resembles a macaroni with a recognizable hole.”

“This seems to all right for the machine,” Kichizi thought.

“However, the next hurdle was the drying method. The product that Kichizi initially produced cracks even if I think it’s done well. He tried putting it in a kettle, and it was mush. Kichizi spent another five years to get the drying method right.”

“After a lot of hard work, the manufacturing and drying methods were finally completed (in 1913). But five years later, the European War (World War I) broke out. When the war ended in 1918 and the recession came, Kichizi Ishizuki found it difficult to manage the production process even though a large number of orders came from the United States.”

Machine used to create domestically produced macaroni. Photo Credit: Hatsue Ishizuki and Kamo City History Compilation Room

Second Generation: Yoshiro

“During this difficult time, Kichizi died of illness, and his son, Yoshiro, eventually took over.”

“Even if the generations changed, the difficult times did not end and within seven years (1926), the factory was handed over and all that remained was a large amount of debt. Yoshiro left his wife and children at his parents’ house and restarted. A series of unfortunate events continued to happen including a catastrophic flood which ruined the new factory.”

“In the summer of 1932 (Showa 7), the inflationary economy in Japan finally ended, and large orders from the United States began to flow in day and night, and the business went back on track.”

Employees working at a macaroni factory in Japan. Photo Credit: Hatsue Ishitsuki and Kamo City History Compilation Room

Third Generation: Continuing the Tradition

“However, macaroni production was temporarily suspended at the dawn of the Pacific War in 1941. During this period, a third generation member of the Ishizuki clan took over the management of the factory.”

“After the Pacific War, the new management revived the business and would later on improve the manufacturing method employed by Yoshiro. This resulted to a monthly production of 10 tons in 1952 (Showa 27) and 30 tons in 1975 (Showa 50).”

“From 1959 to 1960, it seems that one bag containing 360g of macaroni could be bought for about 120 yen, but at that time, eating methods such as mixing macaroni with ingredients were not so popular.”

Employees at the Factory of Kichizi Ishizuki. Photo Credit: Hatsue Ishitsuki and Kamo City History Compilation Room

“The domestic production of macaroni, pioneered by Kichizi Ishitzuki, would later on become one of the major industries in Kamo City where several local factories became involved in the production. However, in the 1970s, mass production techniques were established by major manufacturers, and macaroni, which had been carefully made at small town factories gradually went down.”

“Nevertheless, the production of domestic macaroni, which Kichizi Ishizuki and his descendants struggled to develop, undoubtedly permeated Japanese society and became a comfort food favourite in Japan,” Yasutaka concludes.